Khafre may have, prior to his succession to the Egyptian throne in the 4th Dynasty, been named Khafkhufu, and according to Stadelmann, may have built a large double mastaba (G 7130-40) in the East section at Giza. However, his older brothers, Kauab and Djedefre apparently died early and upon taking the throne of Upper and Lower Egypt, his name was changed to Khafre.

Mariette directed excavations of the pyramid's Valley Temple, which is also related to the Great Sphinx, in 1853. A year later, he was responsible for unearthing one of ancient Egypt's most famous and beautiful statues, that of Khafre on his throne with the protective outstretched winds of the falcon god, Horus, sheltering his head from behind. While Petrie also worked on this pyramid complex while at Giza, the first systematic modern excavations did not occur until the German Ernst von Sieglin expedition of 1909-1910 under the direction of Uvo Holscher. Later in the 1930s, Hassan unearthed the boat pits associated with the pyramid, and in recent times, Lehner and Hawass have investigated the pyramid complex under the auspices of the American Giza Plateau Mapping Project. Their work has mostly centered around modern geodetic measuring techniques, which has yielded considerable knowledge on both the pyramid, and the archaeology of architecture.

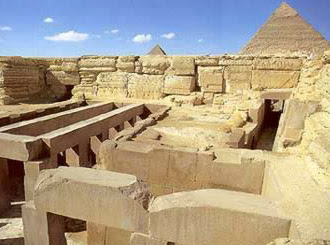

The Valley Temple

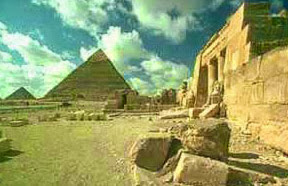

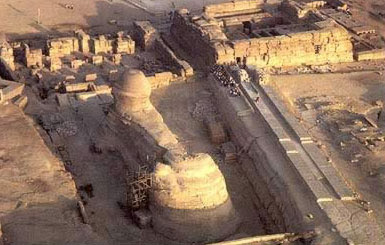

The valley temple of Khafre's Giza complex, which is one of the best preserved Old Kingdom temples in Egypt. As a masterful work of ancient Egyptian monumental architecture, it was cleared of sand and in 1869 this temple, along with other monuments at Giza, became the backdrop for the ceremonial opening of the Suez Canal.

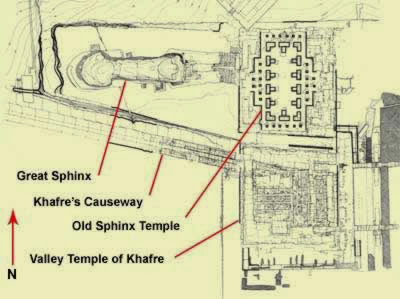

In 1995, Zahi Hawass re-cleared the area in front of the Valley temple and in doing so, discovered that the causeways passed over tunnels that were framed with mudbrick walls and paved with limestone. These tunnels have a slightly convex profile resembling that of a boat. They formed a narrow corridor or canal running north-south. In front of the Sphnix Temple, the canal runs into a drain leading northeast, probably to a quay buried below the modern tourist plaza.

The causeways connected the Nile canal with two separate entrances on the Valley temple facade that were sealed by huge, single-leaf doors probably made of cedar wood and hung on copper hinges. Each of these doorways were protected by a recumbent Sphinx. The northern most of these portals was dedicated to the goddess Bastet, while the southern portal was dedicated to Hathor.

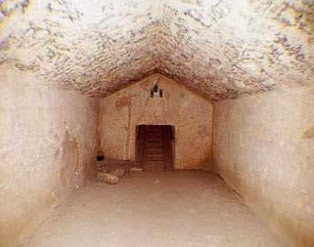

Between the two entrances to the valley temple was a vestibule with walls of simple pink granite that were originally polished to a luster. Its floors were paved with white alabaster. A door then led to a T-shaped hall that made up a majority of the temple. This area too was sheathed with polished pink granite and paved with white alabaster, though it was also adorned with sixteen single block pink granite pillars, many of which are still in place today, that supported architrave blocks of the same material, bound together with copper bands in the form of a swallow's tail. These in turn supported the roof.

On the south side of the roof was a small courtyard, situated directly over six storage chambers also built of pink granite and arranged in two stories of three units each. These were embedded in the core masonry of the T shaped hall. Symbolic conduits lined in alabaster, a material specifically identified with purification, run from the temple's roof courtyard down into the deep, dark chambers below. These symbolic circuits run through the entire temple, taking in both the chthonic and the solar aspects of the afterlife beliefs and of the embalming ritual for which the valley temple was the stage, according to some Egyptologists.

At the other end of the cross in the T shaped hall (north), an opening gave way to a passage, also paved with alabaster, that led to the northwest corner of the temple and there joined the causeway.

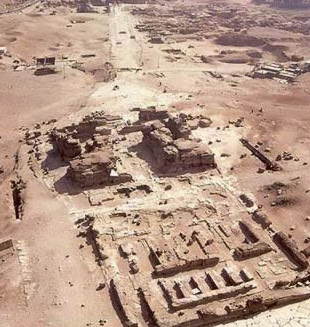

The Causeway

A corridor cut from the rock separated the ruined causeway from the Great Sphinx temple and the valley temple. The causeway stretches some forty-six meters connecting these structures with the the mortuary temple just before the main pyramid. It did not run exactly along the east-west axis of the pyramid and mortuary temple, but instead somewhat to the southeast of it due to the fact that the valley temple was erected slightly out of line with the Great Sphinx and the mortuary temple. Archaeologists believe that causeway was probably a covered corridor built of limestone and lined on its exterior by pink granite blocks. Within it may have been decorated with reliefs.

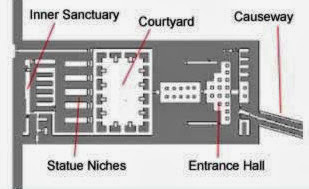

The Mortuary Temple

The causeway enters the mortuary temple near the south end of its front facade.

The entrance to the mortuary temple in the east led through to a small antechamber adorned with a pair of monolithic pink granite pillars. About the entrance area were a few small chambers (two granite chambers immediately to the left of the entrance, and at the other end of a short corridor running along the front of the temple, four more chambers lined with alabaster) that are thought to have been storage annexes or serdabs. Ricke, in his investigation of the mortuary temple, found this area strikingly similar to the valley temple, and considered it a kind of repetition. He designated this area as the "ante-temple" (Vortempel) and the remaining area of the mortuary temple as the "worship temple" (Verehrungstempel).

This antechamber in turn led into the entrance hall itself where there were twelve more similar pairs of pillars to those in the antechamber. This entrance hall had an original ground plan of an inverted T. Hence, the first part of the entrance hall was transverse, with recessed bays. It led in turn to a rectangular section. Off of the transverse part of the hall, two long, narrow chambers branched off from either end, and it has been suggested that huge statues of the king once graced these dim passages.

A door in the west side of the ambulatory communicated with five, long chapels (actually niches) that also originally housed statues of the king. Another narrow corridor opens from the southwest corner of the courtyard and led to an offering hall located in the west part of the temple. The hall was a narrow, long room oriented north-south (in contrast to later mortuary temples) with a false door positioned on the west wall, precisely on the pyramid's long axis. Between the five cult chapels and the offering hall, a group of five storage rooms were provided for cult vessels and offerings used during various ceremonies.

A stairway in the northeast corner of the temple led up to the roof terrace, while in the northwest corner of the courtyard, another corridor led to the paved pyramid enclosure.

Though all of them had been plundered apparently in antiquity, there were five boat bits discovered outside of the mortuary temple. Two of these stood on the north of the temple, while three were to its south. Another pit may have been planned. All of these were carved into the rock in the shape of a boat. Two of the pits still retained their roofing slabs, though all of the pits had been looted, probably during antiquity.

The Pyramid Proper

Kafre's pyramid is surrounded by an inner, huge stone perimeter wall, within which is an open courtyard barely ten meters wide that bounds the four sides of he pyramid proper. This courtyard is paved with limestone slabs of irregular form.

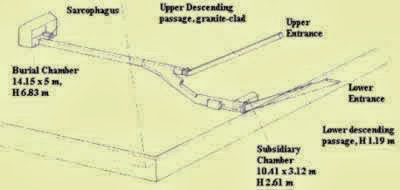

The oldest of the two entrances into the subterranean depths of Khafre's pyramid is now located in the ground about thirty meters north of the pyramid. Carved completely out of the rock subsoil, it is sometimes called the "lower entrance". This portal communicates with a corridor that at first descends before running horizontally. In this horizontal leg of the corridor, a passage gives way on the west wall to a small chamber cut from the bedrock and provided with a pented roof, where part of the burial equipment was possibly stored. After the horizontal section of the entrance corridor, it finally ascends into a horizontal corridor shared by the "upper entrance".

As with earlier pyramids, the burial chamber has a rectangular, east-west oriented ground plan which places it at a right angle to the passage system. With the exception of its ceiling, it was excavated completely out of the rock. Located over the pyramid's base, the burial chamber's gabled ceiling is built from enormous pented, limestone blocks. Originally, the intention may have been to cover the burial chamber's walls of this chamber in pink granite. There are shaft entrances in both the north and south walls of the burial chamber that, at first, appear similar to those in the Queen's and King's cambers of the great Pyramid, but are rather short, horizontal openings that could have been used to reinforce a wooden structure inside the tomb.

The Cult Pyramid

A small, almost completely destroyed cult pyramid (G 2a) sits on the axis of the south side of the main pyramid of Khafre. Cult, or Satellite pyramids as they are sometimes called, are thought to have derived from the south tomb of Djoser's complex at Saqqara, and may have been for the burial of statues dedicated to the ka, or spiritual double, of the king. Originally, it was surrounded by its own enclosure wall. It has a simple substructure that consists of a descending corridor that gives way to an underground chamber with a T-shaped ground plan. Because this chamber contained bits of wood, carnelian beads, fragments of animal bones and vessel lids, Maragioglio and Rinaldi concluded that it must have served as a tomb for one of Khafre's consorts. However, Stadelmann opposed this view, believing that it was a cult pyramid. His opinion is supported by the cult pyramid attached to Khufu's complex on its southeast corner.

More to the point, Lehner believes that the wood made up a frame of cedar in the form of a sah netjer, or divine booth, which was used to transport a statue to be buried in the subsection of this small pyramid.

Other Structures

In the early 1880s, Petrie also discovered west of Khafre's pyramid beyond the so called outer perimeter wall, the ruins of a structure that contained long, mostly east-west oriented rooms. He assumed, as did some later investigators such as Holscher, that this was a worker's village that lodged as many as four to five thousand men in 111 large rooms. However, later work by Lehner and Hawass seem to suggest that that this facility, rather than a settlement, was instead a storehouse as well as the workshops for the pyramid complex. Interestingly, the great number of mollusk shells that were found here also suggest that the surrounding area was, rather than arid desert as it is today, a kind of savanna with the corresponding flora and fauna.

Violation of the Pyramid

Perhaps as early as the First Intermediate Period, as in the case with other pyramids, thieves had probably already broken into Khafre's tomb. Inscriptions by the "overseer of temple construction" indicate that already by the 19th Dynasty, considerable damage had already occurred. In fact, written sources indicate that, on the orders of Ramesses II, casing from Khafre's pyramid was used for the construction of a temple in Heliopolis. Other sources suggest that a large part of the pyramid casing was removed between 1356 and 1362 for use in the Mosque of al-Hassan.

At any rate, the Arab historian Ibn Abd as-Salaam records that the pyramid was opened up in the 774 after the hegira (1372 C.E.), during the reign of the Great Emir Jalburgh el-Khassaki. It is possible that the tunnels going around the granite barriers in the entry passage could have been dug at that time.

The Great Sphinx

Outside perimeter walls may have extended around the entire Khafre pyramid complex, including within it the great Sphinx. Close study by geologist Thmas Aigner of the geological layers of the Sphinx show that it was closely related to the quarrying and building of the Khafre complex.

Hence, there is some indication that it was a part of Khafre's pyramid complex. However, the latter is by no means certain, so here we have avoided the issue for the time being, electing rather to discuss the Great Sphinx separately.

Technical:

Main Pyramid

Original name: Khafre is Great

Date of construction: 4th dynasty

Original height: 1473.5 meters

Angle of inclination: 53o 10'

Lengths of sides of base: 215.25 meters

Length of Causeway: 494.6 Meters

Cult Pyramid

Angle of inclination: 53o 54'

Length of sides of base: 20.9 meters

Hope you you enjoyed reading my post & found it

useful

You may be also interested in